Film, advertisements, the internet – we live in a visual age where we are constantly presented with a vast array of images. Even within a casual chat group between friends, we express ourselves with iconography, peppering our texts with emojis, reaction gifs and memes. It is clear, then, that our students are increasingly immersed in an image-based culture, and visual literacy has become a crucial way of communicating in the modern world. As highly visual members of society, it is integral that young people are given the skills necessary to engage critically with visual media.

Working with comics offers a unique opportunity not only to present complex and nuanced ideas to the students, but also to encourage them to develop skills in critical media literacy. Partnership for 21st Century Skills (P21 – 2009) defined the analysis of media as an understanding of how and why media messages are constructed, and for what purposes. Visual media has vast potential for influencing values, perspectives and behaviours, and in an age of closed-loop YouTube ‘research’ and misinformation, it is increasingly vital that young people are taught to think critically about the information with which they are presented. P21 champion the ‘Four Cs’ of education – Critical Thinking, Communication, Collaboration, and Creativity – all of which can be taught to students in an engaging and empowering way through the study of comics.

People are naturally visual, and we are already equipped to engage with comics even if we know nothing about them. For example, a heart carved around initials on a tree is legible as a combination of text and symbol, and we instinctively understand that the text represents the names of the sweethearts and the heart symbolises the love that unites them (carving into a tree may also give us an insight into the environmental values of the artistic individual, but that is neither here nor there). If you have ever sent an emoticon that expresses something it does not literally represent, read a meme about the Barbie movie, or smiled at the funny pages in the back of a newspaper, then you have engaged with comics. And so, too, have our students, though they might not realise it.

So, what is the benefit of teaching with comics? Well, multimodal reading forces students to slow down, to consider what they are reading. They must engage actively with the combination of text and visuals in front of them, meaning that a passive absorption of only the broadest plot points is unlikely to occur. This is because the text of a comic is incomplete without the accompanying images, and students have to engage in a sophisticated synthesis of the two in order to understand the comic. Additionally, images are open for interpretation in a way that the written word often is not, and by presenting the students with the ambiguity of an illustration, we give them room to engage in rich and complex discussions with their peers. This builds their confidence, eloquence, and ability for collaboration.

Comics also have the benefit of being a lot more fun to read than a four-hundred-page Victorian novel, and it is possible to engage with multiple comics in one module – perhaps even in one lesson – rather than being limited to one novel per term. This offers the students a broader range of subjects to capture their imaginations, and gives teachers a wider array of topics to discuss. As with all forms of literature, it is important to support the students to make their own interpretations and analysis of comics, rather than allowing them to become preoccupied with providing the single, ‘correct’ meaning. Comics can help students to become comfortable with ambiguity, and this is aided by the fact that comics are not currently as well-studied as, say, Jane Eyre or Shakespeare. As a result, students are forced to rely on their own arguments, rather than borrowing the ‘right’ response from pre-existing essays and materials on the internet. A democratic classroom can be created through the introduction of comics in this way, where students feel their arguments and insights are both valued and valuable to the discussion of the medium. Reading comics in this supportive environment develops literacy skills that may also inspire interest in more traditional forms of writing. We can hope that maybe, perhaps, possibly, the students will apply these skills to other forms of literature, and will come to realise that the four-hundred-page Victorian novel is indeed a source of insight and entertainment, just one that is not immediately accessible to modern eyes.

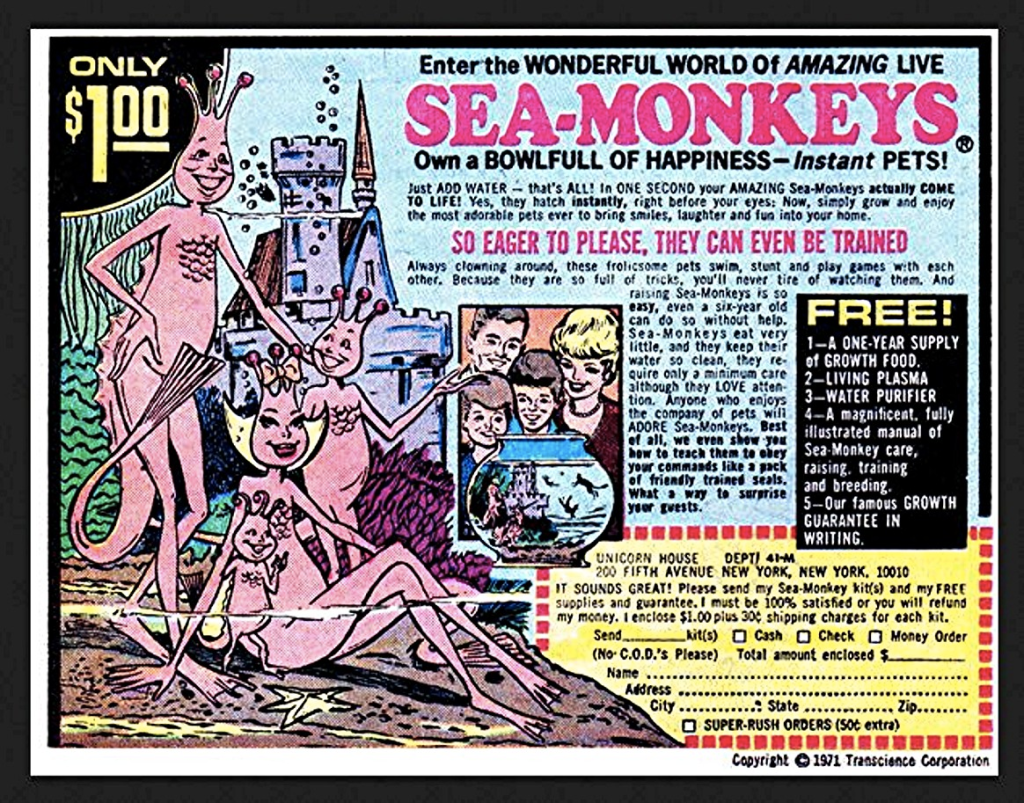

Once they have the visual literacy skills gained by reading comics, the students can assess visual media with more competence, confidence, and critical reflection. When presented with an advertisement, students can identify what behaviours the ad might be attempting to foster in its audience, based on the iconography it employs and the words with which it defines its project. If they come across an opinion piece on the internet that disguises itself as a factual analysis of events, they will be able to identify the core argument of the piece, assess it against their personal knowledge, experience and opinion, and thereby decide if they wish to subscribe to the same perspective as the writer. Similarly, they may themselves become the creators of visual culture. An early training in comics might encourage them towards creative writing and art, true, but reading and analysing comics will give them transferable skills they can carry into the workforce as adults, since many forms of employment require professional presentations that contain visual or multimedia elements.

Comics are a sophisticated and fascinating form of media that extend beyond the bulky superhero, or the cutely anthropomorphised animal. They can express complex social issues in accessible and entertaining ways, and through reading comics with a critical eye, we can understand not only the medium, but the world, a little more clearly. By teaching our students how to read comics, we simultaneously teach them to approach their culture with more confidence, giving them the information, and the skills, they need to be thoughtful and engaged citizens. Furthermore, by reading comics with our students, we encourage them to engage analytically with the society in which they find themselves and – hopefully, maybe, perhaps – we nurture the skills they need to imagine a better one.

Further Resources:

- Diamond Bookshelf: The Graphic Novel Resource for Librarians and Educators.

- Cary Gillenwater, ‘Lost literacy: How graphic novels can recover visual literacy in the literacy classroom.’ In Afterimage, 37 (2), 33– 36.

- Maureen M. Bakis, The Graphic Novel Classroom: POWerful Teaching and Learning with Images (Corwin Press, 2011).

- Partnership for 21st Century Skills

- Jón Már Ásbjörnsson, ‘On the Use of Comic Books and Graphic Novels in the Classroom’ (2018)

- Courtney Donovan and Ebru Ustundag, ‘Graphic Narratives, Trauma and Social Justice’ (2017) 11(2) Visual Research and Social Justice 223

- Thomas Giddens, ‘Comics, Law, and Aesthetics: Towards the Use of Graphic Fiction in Legal Studies’ (2012) 6(1) Law and Humanities 85

- Jérémie Gilbert and David Keane, ‘Graphic Reporting: Human Rights Violations through the Lens of Graphic Novels’ in Thomas Giddens (ed) Graphic Justice: Intersections of Comics and Law (Routledge 2015)

- Paula E Griffith, ‘Graphic Novels in the Secondary Classroom and School Libraries’ (2010) 54 (3) Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy 181

- Amine Harbi, ‘“He Isn’t an Animal, He Isn’t a Human; He Is Just Different”: Exploring the Medium of Comics in Empowering Children’s Critical Thinking’ (2016) 7(4) Journal of Graphic Novels and Comics 43

- Chris Murray and Golnar Nabizadeh, ‘Educational and Public Information Comics, 1940s–present’ (2020) 11(1) Studies in Comics 7

- Gretchen Schwarz, ‘Graphic Novels, New Literacies, and Good Old Social Justice’ (2010) The Alan Review 71

We’ve also put together a recommended reading list for teachers here.

Written by Alex Carabine

Leave a comment