DC Special Series Vol 1 #15 June, 1978 Source: Batman Reddit

Before you begin reading this blog, you may want to take a look at Hannah’s excellent post on this Batman narrative, which explores the legality of the situation that Batman has found himself in. It’s fascinating and enjoyable, and it even includes the law of the sea! My post (the one you’re reading right now) is a companion piece to Hannah’s, where I will analyse the comic from a humanities’ perspective. That is, after all, what I do.

If you’ve ever wondered how on earth you would begin close reading a comic, this blog will be a great place to start. I’m going to look at panel composition, word choices, sentence structure, the narrative… all sorts of good stuff. Whether you’re a teacher wanting to weave comics into your classroom, or even an undergraduate wanting to pick up some tips for your graphic novel module, I hope you will find what you need here! And if there’s anything confusing, or if you need further clarification, drop a comment and I’ll answer all your questions as best I can!*

(*Beware, undergrads: I will be able to tell if you’re trying to get me to write an essay for you. I’m wily like that.)

Source: Batman Reddit

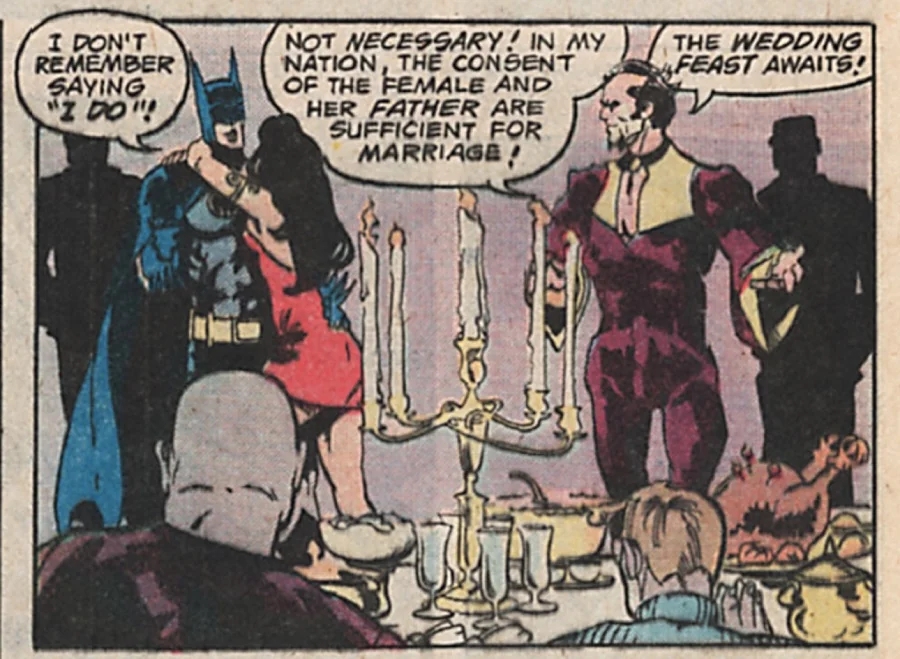

Have a look at the above panel from the 1978 Batman comic ‘I Now Pronounce You Batman and Wife!’. When Westerners read comic books, our eyes naturally begin in the top left of the page/panel/image, and then drift across to the right, gathering visual and literary information as we go (note, this is not the case for manga, which obeys Japanese reading conventions and moves from right to left). Anything placed in the left of the panel, therefore, is prioritised, as it is the first thing a reader will pay attention to.

Here, that’s a speech bubble by Batman. ‘I don’t remember saying “I Do”!’ he’s protesting, as a woman in a red dress drapes herself around his neck. By giving us Batman’s perspective first, the comic creators are prioritising his experience of events. In terms of forced marriage, it’s worth nothing that Batman was taken to his own wedding under duress, since he was drugged and barely conscious at the time. Consent under the influence is still consent, if the substance that influenced the person was taken voluntarily. But Batman was boobytrapped into taking the drugs (knockout gas was implanted into a punching bag), and if he was barely conscious during the ceremony? That doesn’t sound like true consent. This, then, has the makings of a forced marriage.

Take a closer look at the speech bubble itself. The boundaries of the bubble interrupt the lines of the panel, breaking free of the borders that are meant to contain it. This further emphasises the speech bubble, not unlike the way WRITING IN ALL CAPS FEELS LIKE YELLING. By disrupting the frame, the artist is visually representing the way in which the dialogue is conveying a disturbing piece of information, and thereby expressing Batman’s own disorientation. He is not in alignment with what is happening around him, and nor is his speech bubble.

Now we have read the bubble, our eyes are naturally drawn to the speaker: the Bat himself. His body language is suggestive, as he stands rigid, unyielding, with his hands apart and his head drawn back. If we saw this pair at a bus stop, we would instinctively know that the man was not happy in the situation, and that the woman was perhaps being uncomfortably affectionate. Talia’s body leans strongly towards Batman (even her left knee juts towards him, which is perhaps a bit threatening to a gentleman), and although it’s alluring (a red dress and a short skirt are rather cliché signifiers of a sexy, sexual, or sexualised woman), it’s also claustrophobic. Smothering. This is an invasion of Batman’s personal space, and as readers with empathy we might feel uncomfortable looking at the pair: we, too, may remember moments when we have been embraced by someone we would prefer to keep at a distance.

The contrast between Talia and Batman is emphasised by the panel’s use of colours. Take a look and see what you notice, and what your brain has probably already subconsciously picked up on. Talia, Ra’s al Ghul and the rest of the panel are dominated by warm tones: there are reds, pinks, oranges and yellows. There is known psychology behind colour theory: red is a primary colour, and it is associated with danger and threat, as is yellow and orange. Consider how these colours are used by nature to warn onlookers:

Coral snakes have one of the most potent neurotoxic venoms in North America. Image source: Jay Ondreicka/Shutterstock.

Batman, by contrast, is cobalt blue and black. On the one hand, this could just be colour theory in practice (what’s the best way to make a blue character stand out? Juxtapose him against his opposite colours, orange and red). However, it also serves a symbolic purpose: not only is Batman vulnerable in this situation, but he is also an outsider even within his own panel. This forces the reader to focus on him again: his experience of events is the key.

As our eyes move away from Batman and Talia, we encounter the candelabra. It seems a bit of an awkward gap, but it serves to break up the composition and put Batman and Ra’s in opposition. They are the two men of Talia’s life, and, as is traditional to many forms of wedding ceremony, Talia-as-bride has crossed the divide from her father’s world into the groom’s (her back is literally turned to Ra’s as she embraces Batman). This also indicates that Talia is an ambiguous figure, that she is neither completely good, nor utterly evil, but can move between the two moral positions.

Finally, we read Ra’s response to Batman’s speech bubble. ‘Not necessary!’ He pronounces. ‘In my nation, the consent of the female and her father are sufficient for marriage!’. What a horrifying lack of agency for Batman. And this might shock the reader, as we are so used to Batman having all the cultural forms of power available in the Western world: he is white, male, rich, physically strong and heavily armed. Ra’s stating that Batman’s consent is ‘not necessary’ utterly dismisses and disempowers him. This is not his world, it is Ra’s ‘nation’. Batman has been removed from his culture, and suddenly he has no say in proceedings.

Traditionally, we might accept this as being the fate of women and girls because they are predominantly the victims of forced marriage (though truthfully it can happen to anyone of any gender, sexuality or background). What I mean by ‘accept’ is that we wouldn’t necessarily be as shocked by Talia being forced to marry Batman as we are by Batman being forced to marry Talia, because we’re used to the idea of women being treated as commodified objects of exchange. The narrative deliberately goes against the (cultural) grain to make readers feel uncomfortable. One of the reasons for this discomfort is that, by putting Batman into a traditionally female position, the comic is feminising Batman. After all, his masculinity is even encoded in his very name. His gender expression of traditionally valuable masculine traits (strength, intellect, courage, amongst others) is crucially important to his character. But it would also be significant to his readers, who in 1978 would have predominantly been young men.

Thankfully, Talia isn’t empowered over Batman. Whew! The gender hierarchy is still in place. Her father refers to daughters in his nation – and, by extension, his own daughter Talia – as ‘the female.’ Referring to women in this way dehumanises them, as a female is a biological category, not an entire human being with thoughts, feelings and opinions. Ra’s isn’t concerned with his daughter’s interests, he just wants Batman as his son in law. Talia is a pawn, and it’s a happy accident that she loves Batman. It is ‘the female and her father’ who are important in Ra’s nation, which means that ultimately the bride is still dependent on male authority within their culture.

Let’s move on to the full page:

Source: Batman Reddit

We’re going to ignore the fact that Lurk is trying to spy through a Yale lock, and move on to the panels containing Batman and Talia. Beginning with the one that says ‘INSIDE…’

Again, we follow the unconscious rules and begin in the top left. It’s unclear who is speaking, initially; Batman is closest to the bubble so we assume it could be him. Then we realise he is actually the subject of the bubble: ‘There is no man your equal’. So, the bubble is emphasising how unique, powerful and masculine Batman is. No man is his equal. This is more familiar territory, and is probably quite soothing to the original (young male) readers after the initial shock of the very first panel. The second speech bubble seems to highlight Talia’s own qualities: ‘Therefore, you are the only man I can love!’ She knows her own value, and so Batman is the only suitable paramour for her. However, the placement of the two facts – 1. Batman has no equal, 2. Thus, Talia can love only him – actually serves to emphasise Batman’s value. If a remarkable woman like Talia loves Batman, how Super Cool and Important he must be. Her love acts as a frame to Batman’s status. Following these speech bubbles leads us from Batman (the subject) to Talia (the speaker). Batman is fully clothed (even unto his cheekbones), but Talia is bare shouldered with her hands behind her neck. She seems to be untying her dress.

After this, our eyes swing left to Batman’s speech bubbles. The first occurs immediately next to his face, then the connections between the bubbles lead us across the gutter into the next panel. This is an ‘aspect’ panel, which shows a different view of the scene that is nevertheless occurring in the same moment of time as the dialogue. Our eyes follow the interconnected bubbles, leading us into the panel where we are given visual information about the scene. Thus, Batman’s speech enacts a kind of striptease, where each linked bubble is like the removal of a piece of clothing. That is to say, they delay gratification and lead us to the visual information that Talia is – gasp! – actually naked. We know this for sure because her dress is pictured on the bed. Now, the reader is visualising Talia naked within the scene, and the gutters (where the reader’s imagination is doing the work) act like the fans in a burlesque performer’s dance. They hide Talia’s body, even as we’re intensely aware of its presence in the scene.

Presence, and also vulnerability. Remember: Batman remains fully clothed, and therefore empowered. He is beginning to find his footing as a hero again, as the power dynamics shift into his favour. And what he is saying within his speech bubbles seems to extol Talia’s virtues: she is beautiful, intelligent, and loyal. Sounds great, right? Except ‘Beautiful’ comes first in the list, so her appearance has the most significance for Batman. Then ‘intelligent’ – thank goodness, someone actually values Talia for her mind! Though, after all, we wouldn’t expect the Batman to be satisfied with the company of a woman who couldn’t keep up with him. And then we have ‘loyal’. Loyal? That positions her as valuable only in relation to Batman (or… her dad? How do we know she’s loyal? Who is she loyal to, and how has Batman come to this assessment?). It also has a similar energy to ‘monogamous’ or ‘stand by your man’, meaning that Batman wouldn’t have to worry about her leaving him. So, two out of the three personality traits given to Talia actually emphasise how she makes the men around her feel. Ick.

Furthermore, Batman rejects the marriage by saying he can’t ‘consider it real’. That’s an interesting choice of words: he is inscribing his own personal reality over the cultural reality of Ra’s, indicating that Batman’s opinion is as powerful as Ra’s’ cultural laws. Step by step, Batman is reasserting his power, and this is violently expressed when he punches Talia in the face, knocking her unconscious. He apologises, but is that enough to excuse this sudden burst of (what could be construed as domestic) violence? He has been systematically disempowered through the previous panels, true, and so this punch might feel justified to certain readers. But let’s remember, it was his first course of action. He didn’t ask Talia to consider his position and he didn’t ask her for her help. He just punched her in the face. And the fact that Batman is physically powerful enough to knock Talia out with one blow begs the question – how disempowered was he in this situation, really? And is violence like this permissible when it’s a superhero swinging his fists instead of ‘just’ a man? Are there different rules for vigilantes, as long as they apologise, as long as they have a mission? If so, this justifies violence, and makes it subjective. Which is an uncomfortable conclusion, and, in my opinion, makes Batman questionable as a hero.

Now let’s consider the final three panels. The first two are one image divided: we see Talia, still clearly naked, lying unconscious at Batman’s feet. The gutters do their work again, and we can imagine Batman towering over the vulnerable woman: he is fully dressed in superhero armour, martially trained, male, and conscious. All the power in this scene belongs to him now.

It’s at this point in my analysis that I find it useful to think about the world or cultural moment in which art, literature, film, etc. is produced. What was happening culturally in the 1970s, particularly in America where this comic was produced? Can we see any ways in which this could be informing the narrative of the comic?

Briefly, the 1970s were a time of great gender upheaval. In America, Gloria Steinem, Kate Millett and Susan Brownmiller published books and articles, made TV and radio appearances, all advocating for women’s equal rights. In August 1970, TIMESpublished an article entitled ‘Who’s Come a Long Way, Baby?’ in which they state:

‘They want equal pay for equal work, and a chance at jobs traditionally reserved for men only. They seek nationwide abortion reform —ideally, free abortions on demand. They desire round-the-clock, state-supported child-care centers in order to cut the apron strings that confine mothers to unpaid domestic servitude at home. The most radical feminists want far more. Their eschatological aim is to topple the patriarchal system in which men by birthright control all of society’s levers of power—in government, industry, education, science, the arts.’

Of course, this Second Wave Feminism began in the 1960s and continued through the 1970s, and didn’t exist without cultural backlash. And one such arena for this backlash was advertising. All that to say, when I first saw those panels of Talia lying on the carpet at Batman’s feet, I was reminded of this infamously sexist advert from 1970:

Source: Business Insider

To be clear, I am not saying that the comic books creators were actively, maliciously misogynistic in the way that the ad designers certainly were. Nor am I saying that they were consciously referencing the above advert. I am instead highlighting that the comic is a product of its cultural moment, and that cultural moment comes weighted with certain attitudes towards women – especially women who were encroaching on traditional male territories of power (like autonomy in sex and marriage). Talia is a remarkable woman, and it isn’t a stretch to see her as representative of the aspects of feminism that deeply disturbed men in the 1970s (and, sadly, today). This narrative began by feminising Batman, by making Talia contingent to her father’s power. It ends with Talia, unconscious and naked at Batman’s feet, a victim of his violence.

Finally, the fork as lock pick. It isn’t beyond the realms of Freud to read this as a sexually suggestive image. By the final panel, Batman has fully dominated the scene in all the usual heteronormative, patriarchal ways and is once more a hero. Supposedly.

And that, dear readers, is how you can close read a comic. If you would like to make a start for yourself, grab a comic and ask the following questions of its pages:

- What is happening in the narrative?

- What is happening in the images, and why is it significant?

- What was happening in the world when this comic was produced, and how might the comic be responding to those events?

Happy reading!

Written by Alex Carabine

Leave a comment