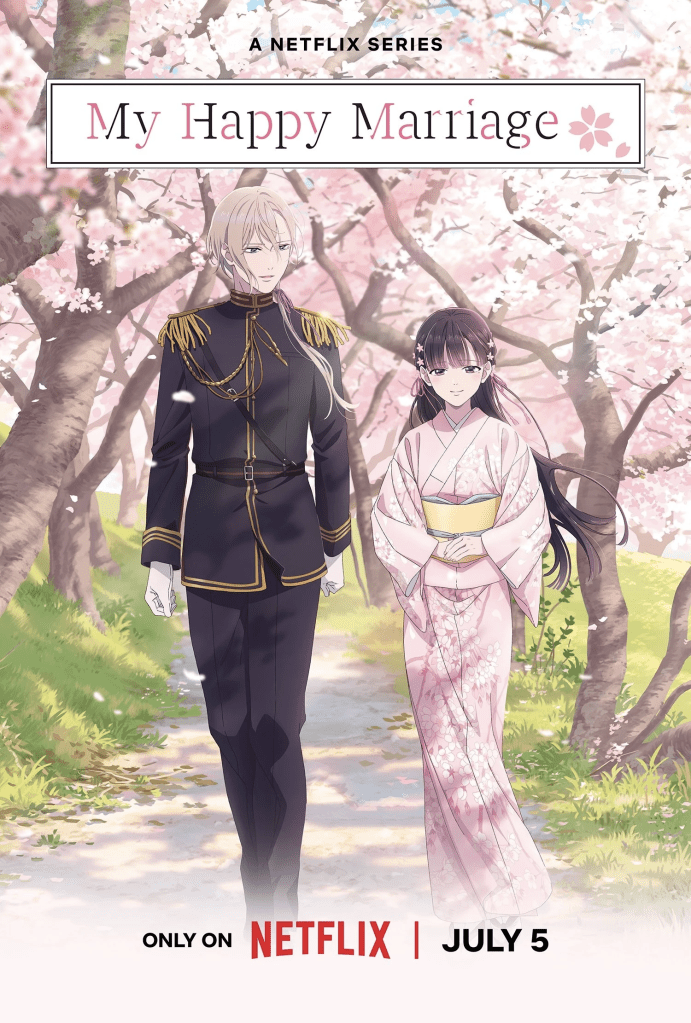

Because I enjoy anime, Netflix’s algorithm has been hurling constant reminders at me about a new series: My Happy Marriage. I had dismissed it as of no interest to me, as I don’t tend to enjoy shōjo anime (given that I am a spooky-hearted thirty-something and the demographic of shōjo is bright teenage girls, this is perhaps no surprise). But viewing it from my role as a research assistant for the Drawing on Forced Marriage project, the title caught my eye. After all, arranged marriages – and forced marriages – are a staple of the romance plot. Perhaps this would be no different. Within an episode, I realised my assumption was correct: the entire narrative of the anime hinges on various forms of arranged and forced marriage

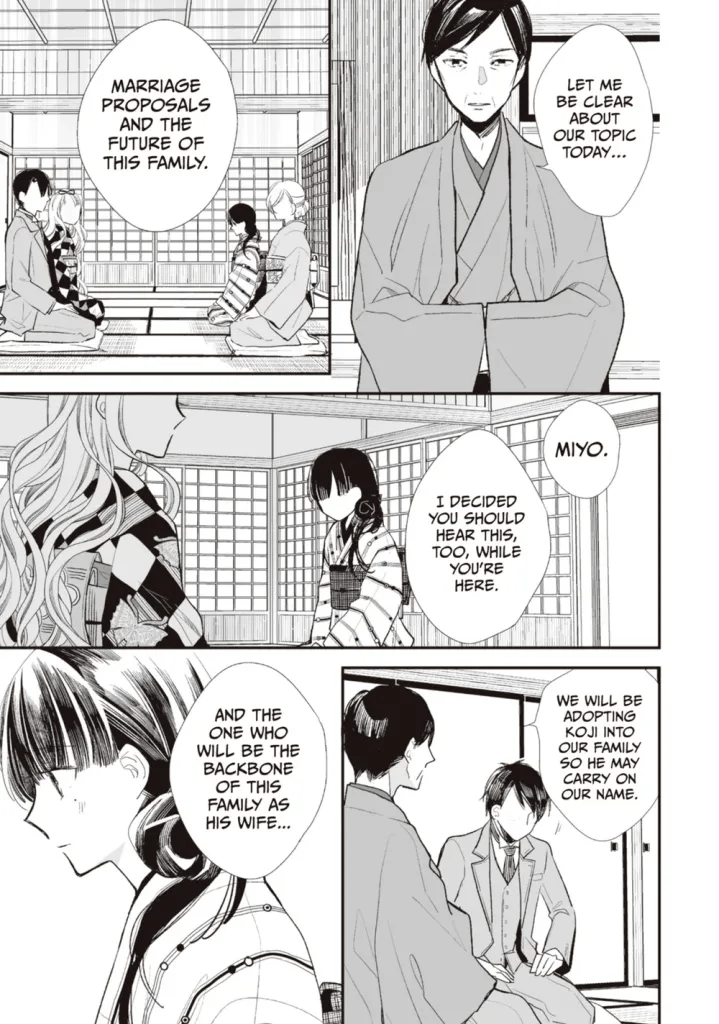

Briefly, the anime is a fantasy/historic romance, set in in a version of Japan where supernatural abilities are an inherited trait, like curly hair or height. Miyo is the Cinderella of the story: she is mistreated by her family, which comprises of her father, her stepmother, and her half-sister, Kaya. Miyo has a male friend, Koji, and both seem to have feelings for the other. However, Koji is betrothed (by his family, and somewhat against his will) to Kaya, and Miyo is told by her family that she must marry Kudo. Koji and Miyo may care for each other, but they may not get married.

With me so far? Good.

Miyo and Koji both illustrate some key facts about forced marriage: it can happen to any gender, and for many reasons. For example, Koji is marrying into Kaya’s family, not the other way around. This is actually, historically speaking, a traditional practice in Japan: when a family lacks a male heir, the groom might take his wife’s name and enter her family home in order to take over the family business (this is especially the case for artisans and craftsmen, who need to pass down their skills to the next generation). Miyo is a different case, as her family are, in effect, trying to get rid of her. Because she has not inherited any supernatural abilities from either parent, her family does not value her. Later, the audience also discovers that Miyo’s (now deceased) mother and father were themselves a forced marriage. The father reveals that the pair never loved each other even after their marriage, and so could not love his daughter as a result.

Koji’s situation shows how agreement is not necessarily consent. In episode 1, Koji’s father tells his son that ‘you must follow this decision for the sake of the prosperity of this family.’ As will be seen in the teaching pack on forced marriage, family benefits can be a concern in the planning of a forced marriage. Once he knows of his family’s plans for him, Koji apologises to Miyo: ‘I’m ashamed of my cowardice. In the end, I couldn’t do anything.’ The emphasis on ‘cowardice’ demonstrates Koji’s frustrated wish that he could change the course of events; however, his acknowledgement of powerlessness indicates that his consent and agency have been stripped from him by his parents.

Miyo’s narrative certainly follows the Beauty and the Beast plotline, at least initially. Upon being told that Miyo will marry Kudo, her sister Kaya cruelly announces ‘I’ll look forward to seeing how many days you’ll last being his wife.’ There are hints of violence and cruelty, that Kudo is ‘rumoured to be a cold and merciless man. Every fiancée has run away from him.’ It is important to note that not all forced marriages are violent, and that the nature of the relationship (healthy, unhealthy, or abusive) does not determine whether the relationship is forced or consensual. But within this romance, Kudo is the Beast, and Miyo must go to his castle.

One thing the anime takes care to emphasise is how traumatised Miyo is by her family’s treatment. Whether she has the ability to accept or refuse the marriage is impossible to ascertain: she is softly spoken, seldom raises her eyes, and apologises when her family abuses her. As such, her mental health does not seem robust enough for her to act in her own interests, and her family’s treatment indicates that she could not refuse the marriage.

On first meeting Miyo, Kudo states that ‘While you’re here you must absolutely follow my orders. If I tell you to leave, you leave. If I tell you to die, you die. I won’t listen to any complaints or objections.’ There are forms of slavery-like marriages, where one of the spouses is controlled by the other to the extent that they are treated like property, and Kudo’s sentiment leads to anxiety that this might be the case. I was shocked when Miyo agreed to these horrifying terms, bowing her head in acceptance. Thankfully, Kudo has the decency to look surprised, and the anime begins to play a careful game of making the relationship look forced whilst emphasising that, firstly, Kudo is not as villainous as his reputation (thank goodness), and, secondly, Miyo actually has some agency in the situation. For example, they live together before they are even formally engaged (with a servant as a sort-of chaperone, so no worries about any funny business), and the pair even go on dates to get to know each other before they choose to become engaged.

However, it is acknowledged that if Miyo runs away from Kudo, she will not be welcomed home. In the real world, objecting to a marriage can lead to the person being excluded from their family and community. Fearful of becoming isolated, this might lead to the person ‘agreeing’ to the marriage in order to maintain their relationships (as Koji certainly did). Without any support system, could Miyo leave Kudo, even if he were fully evil? I doubt it. Thus, the romance tropes of forced marriage – two people brought together against (at least) one person’s will, a reluctant blooming of feelings between the pair, conflict arising from their differences – are present in the plot, even while the audience’s conscience is soothed.

From what I’ve gathered from romance novel blogs, the appeal of this situation is watching how love can slowly develop between two people who originally have no feelings for each other – or, indeed, who actively hate each other, as in the ‘enemies to lovers’ story arc. But in the real world, it is consent, and not love, that is at the centre of a forced marriage, so these plots rely on a non-consensual act to develop the narrative. Which is troubling, to say the least. And though it’s true that not all forced marriages will lead to damaging living situations, they can still have serious effects on the freedom and well-being of the people involved.

Having this romance plot be so prevalent is one thing, but My Happy Marriage is rated 12+ and aimed at girls. These are very young adults to be romanticising this kind of plot. But then again, even the Prince in Cinderella was pressured into searching for a fiancée by his parents, so children learn about forced marriage in the nursery. Teaching young people critical thinking skills is a great step towards empowering them to defend their own agency, and to know that finding such storylines romantic is one thing, but engaging in them – or watching a friend engage in them – is another.

Which makes the (at time of writing) final episode of My Happy Marriage rather interesting. Between ‘Episode 6: Determination and Thunder’ and telling Miyo to basically prepare to die in the second episode, Kudo has been revealed to be a thoughtful and generous person. He has noticed how Miyo has been wounded by her family, he has recognised her intrinsic value, and he has gently tried to persuade her to value herself. It’s genuinely very sweet, if a little… paternal. In episode 6, Kaya wants to swap fiancés with Miyo, having ambitiously fallen for Kudo herself. She and her mother kidnap Miyo, and, in a scene symbolic of torture, cut Miyo’s beautiful kimono to pieces in an attempt to force her to relinquish her engagement with Kudo. By emphasising Miyo’s agency in her decision to marry, the parameters of the previously forced marriage shift, and Miyo and Kudo’s relationship becomes an arranged marriage. They did not choose it themselves to begin with, but they are choosing it now. Miyo, having gained some confidence, refuses to give up her engagement, and begins to identify her own self-worth. As is typical of romance, Kudo storms into the building where Miyo is being held captive and rescues her in a daring display of supernatural prowess. Thank goodness.

The anime is being released one episode per week on Netflix, so I can’t end this blog post with a mic drop that summarises the whole series. But what I can say is that media like the anime, like the manga it’s based on, and like comics in general, offer us an excellent way to begin these conversations with young people. What is a forced marriage? How is an arranged marriage different? Where do you place your self-worth? What does a loving relationship look like? And although cute animes like My Happy Marriage aren’t responsible for the occurrence of forced marriage, perhaps they can be used as vehicles through which forced marriage can be discussed, and stopped.

If you want to learn more about the facts of forced marriage, then read this post by Hannah.

Written by Alex Carabine

Leave a comment