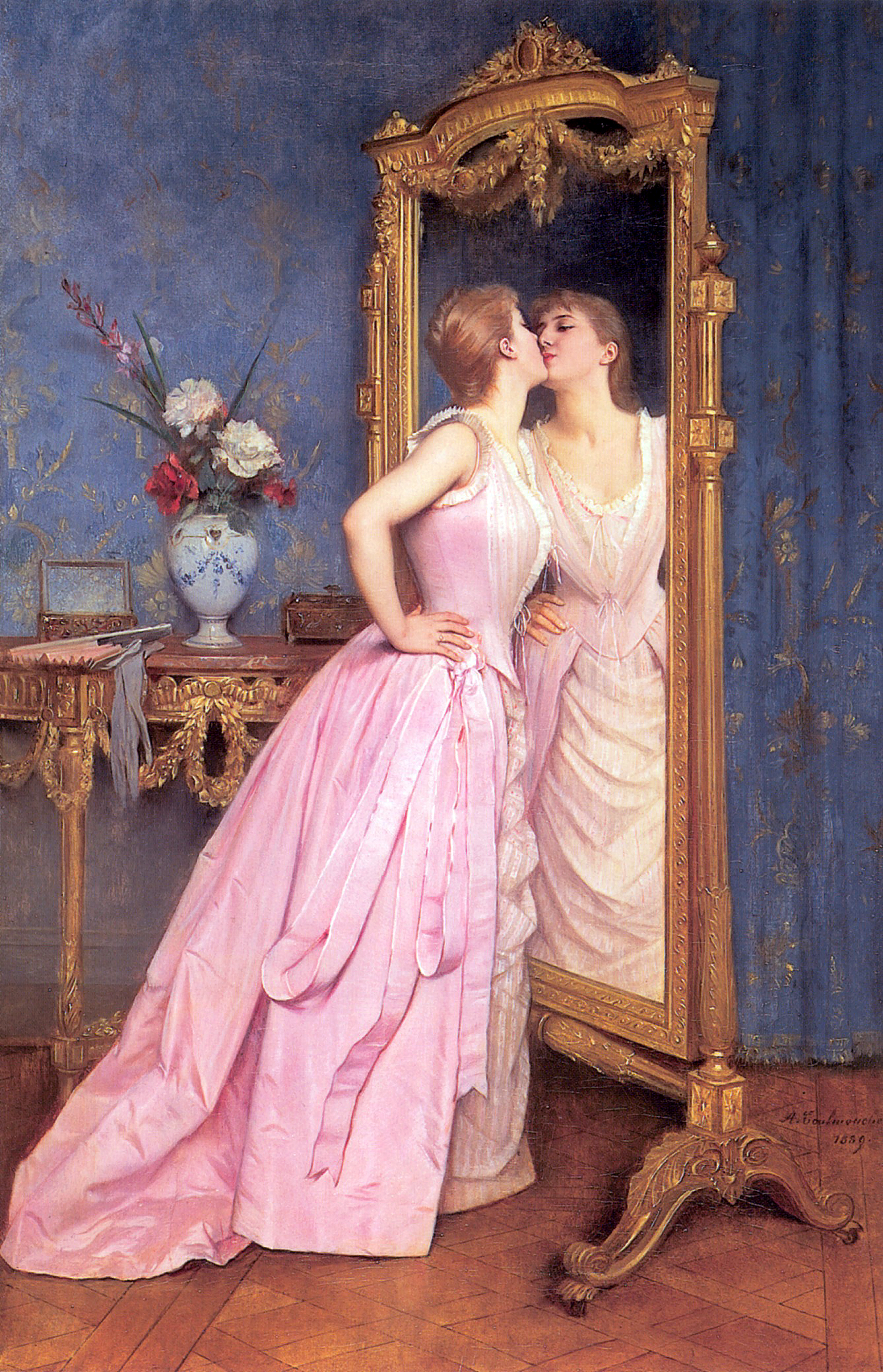

We can learn a lot about a culture from their art. What do the people value? What stories do they tell? When we answer those questions, we learn a lot about an era. Nineteenth-century portrait artist Auguste Toulmouche was known for his paintings of beautiful, indolent women. In fact, Émile Zola (an author and playwright of the naturalism school) dubbed the women in Auguste Toulmouche’s paintings as “delicious dolls”. They are luxurious portraits of upper- middle-class women from Paris, who recline their way through languidly domestic scenes. Their faces are often turned away, their figures composed to display their dresses rather than their inner world, and occasional glimpses of personality tend to be limited to romance (see: The Love Letter, 1883, above). Toulmouche was a popular artist, so we can infer that his audience enjoyed beautiful, uncomplicated women, preferred lavish scenes, and that the scenarios depicted probably represented the audience’s own life (only the wealthy had easy access to leisure activities like art exhibitions).

Don’t get me wrong, the paintings are beautiful and Toulmouche’s skill is exquisite (look at the gleam on that silk! The saffron jacquard of the chair! The chinoiserie of the blue screen!). Yet, I must confess, I find his women to be pretty but bland.

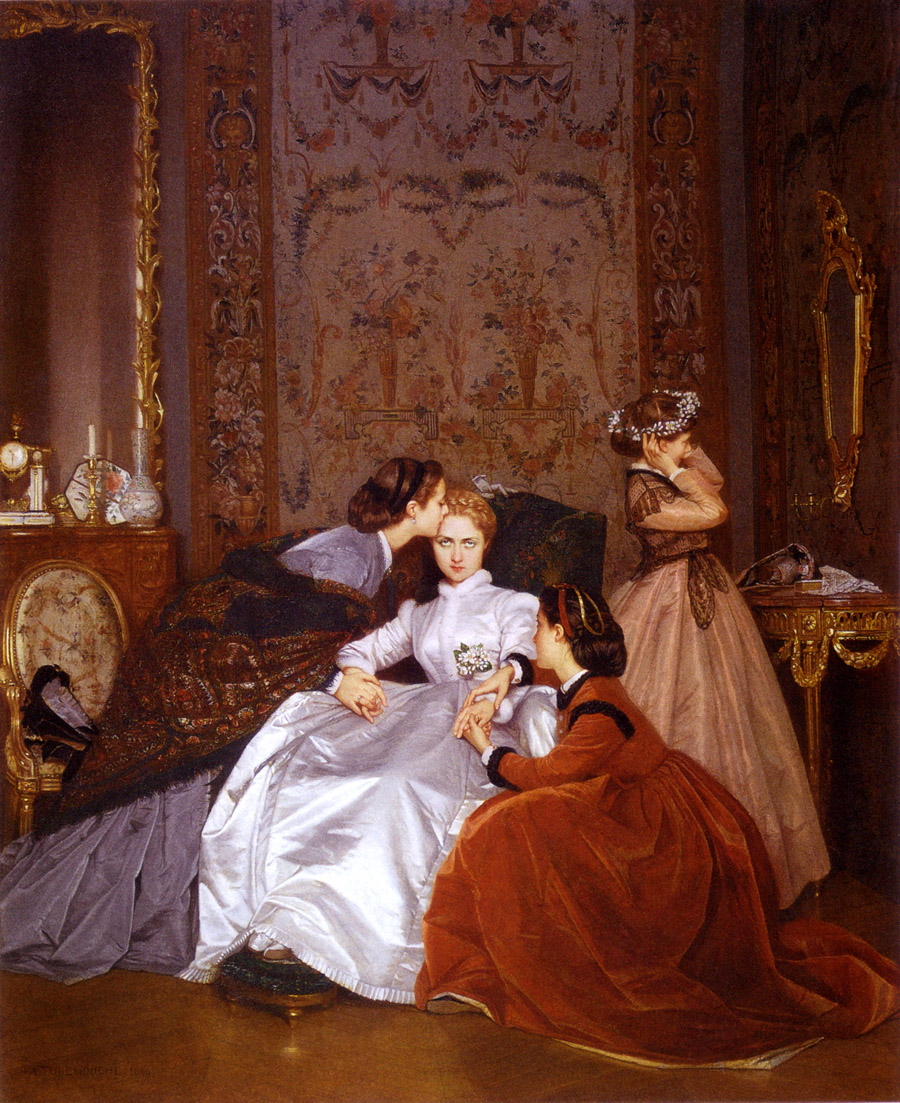

Not so The Reluctant Bride (1866), which must have taken Toulmouche’s audience by storm. Not only does the eponymous young woman subvert expectations of Toulmouche’s oeuvre, but she challenges culturally received notions that weddings are sweet, happy and sentimental affairs.

The painting depicts a moment that seems to be ‘behind the scenes’ of a wedding. Three women form a party around the bride: one crouches at her feet, holding her hand and incidentally highlighting her wedding ring. On the left, another woman has just arrived and is dropping an earnest kiss on the bride’s forehead. In the background, the most tragic figure of the scene: a young girl, trying on the bride’s crown of orange blossoms. We’ll get to her by and by.

Compositionally, the scene is constructed to highlight the bride. It is dominated by shadowy, russet tints, and the corners are darkened by a vignette effect. The edges of the painting therefore seem to close in on the bride in the centre, who is luminous in her white dress. And what a dress! It is decadent silk and fox fur. The expensive fabrics and extreme whiteness indicate her wealth and status, as poor women didn’t have the luxury of spotless white silk (we’re too busy getting stuff done and might get dirty. Bitter? Moi?). Despite its costliness, the dress is minimal to the point of severity, which is unusual for the overblown tastes of the mid-nineteenth century. Take a look at her collar and how snug it is to her throat, surrounding her neck from collarbone to jaw. The fur looks soft, but the cut looks like a snare.

And then of course, there are her eyes. She stares, deadpan, directly at the viewer. No smile softens her face, no blush warms her cheek. Her expression is an unusual level of challenge, as it wasn’t common at this point in time for models to ‘break the fourth wall’ with their gaze. Admittedly, it wasn’t unheard of in Toulmouche’s later work, but consider the artist’s typical delicious dolls, with their averted faces:

Back to The Reluctant Bride. Her expression is quite a shock by comparison. From her attitude, combined with the painting’s title, we can infer that she did not want to get married. That the women around her are, what, attempting to comfort her? Reconcile her? Coerce her? Some culturally specific equivalent of all three that English can’t express in a single word?

And why wouldn’t she want to get married? At this moment in the analysis, I’m going to swing from the France of Toulmouche, across the Channel, to Victorian England. So please understand that when I present the following facts, they apply to Britain and were therefore not necessarily universal to Europe and America (though they still speak to broadly held cultural attitudes).

Firstly, when it came to marriage, women didn’t have much choice, and they were raised to see marriage as a natural culmination in their narrow lives. In fact, there were a wealth of manuals aimed at middle class women to encourage them to marry, and to teach them how to be good wives. William Andrus Alcott’s 1837 book The Young Wife, or Duties of Woman in the Marriage Relation, stated that:

“There was a time, in the history of our world, when woman did not exist. Man was not only alone — without a companion — but destitute of a ‘help-meet’ — an assistant. In these circumstances, almighty Power called forth, and, as it would seem, for this very purpose, that modified, and in some respects improved form of humanity, to which was afterwards given the name of woman, and presented her to man. She was to be man’s assistant.”

Delightful. Women were defined by their culture and religion as secondary to men, dependent on men, and spiritually obliged to help men. And, as it’s difficult to be what you can’t see, most girls weren’t presented with many other options, and so could only imagine themselves becoming wives. The ‘marriage relation’ (as Alcott titled it) was sold as a romantic ideal to women, especially in art. Consider the painting below: ‘Finally Alone’, by Edoardo Tofano (1887):

Finally alone. The pair are clearly devoted to each other, have perhaps endured a day of celebration with their family and now, at last, can hold each other and find the first moment of married peace. See how she leans against his chest? That’s how women should be, in this era. Beautiful, charming, but delicate. See how strong and manly the groom looks, with his handsome beard and the paternal kiss he rests on her forehead as he supports his weary bride? What an ideal of nineteenth-century masculinity. Like the reluctant bride, this woman’s dress is also conservative (even her fingertips are covered), but look at all that lace, at the veil tumbled over the chair. This is a proper bridal pair: lavish, tired by their celebrations, but deeply in love. May they live happily ever after.

(Though, to be honest, there’s something defeated-looking in this bride’s pose. Look how she’s rigid and upright within the embrace. Is she happy to be there? Did the artist think to wonder about his characters?)

Women, then, had few options presented to them, and marrying also came with the potential bonus of benefiting their family. Perhaps their marriage could act as a business alliance between the bride and groom’s families. Or maybe by marrying well, the bride would open up a world of better suitors for her younger sisters, or employment opportunities for her brothers. Marriage was not simply a union of loving hearts; rather, it was a brokered deal between multiple interested parties.

And because marriage was a tricky business, men were encouraged to wait to get married, as taking a wife was very expensive. Women couldn’t work (the scandal!), and they might not bring a consistent income in the form of dowry or annual settlements from their family. One man’s income had to be enough to support a whole household, and to support them well (status was so important to the middle classes). Because of this, men would delay marriage until their careers were secure, meaning they were often in their middle age (or older) by the time they turned their thoughts to wedlock. Women, on the other hand, often had nothing but youth and a modest income to recommend them, so they were encouraged to marry as soon as possible (to be twenty-five and unmarried was horrifying). Exaggerated age gaps were common, as was financial dependence.

Working class women could, would, and did work, and there is historical evidence to suggest that often a baby would be born around the same time as its mother got married. We can hope, then, that working-class women loved their husbands – at least, at the start. Middle class women, however, absolutely could not work. To do so would bring shame on their families. As the middle class became more prosperous, the wives had to become more idle, as their ornamental nature itself connoted status (hence, Toulmouche’s domestic dolls). And education? The idea of women entering university terrified the public, especially as it was posited that increased blood flow to their brains would lead to decreased blood flow to their uteruses, leaving them sterile and thus ruining the future of England.

I didn’t make that up. Sorry.

Women would become masculine, men feminine, and the whole world would end!

At the time of The Reluctant Bride, married women essentially became the property of their husbands. Upon getting married, everything they owned went to their spouse (including conceptual property like copyright). The husband and wife became one person under law – specifically, the husband’s person. Victorian women got married and, in the eyes of the law, ceased to exist. Thankfully, this changed in 1882 with the Married Women’s Property Act. But at the time of her wedding, our reluctant bride would have been staring down the barrel of an existential crisis. And divorce? Impossible, unless the wife could prove infidelity and cruelty (domestic abuse). Which usually required two (male) witnesses.

No wonder she’s reluctant!

Which leads me to the girl in the background of the painting, trying on the crown of orange blossoms. I find her the most tragic, because she has been successfully conditioned into considering marriage as the be-all and end-all of a woman’s life. She is in the same room as a young woman who is clearly devastated by her future, even as she stares defiantly at the viewer. But the reality of the reluctant bride isn’t enough to shatter the fantasy of happily ever after for the orange blossom girl.

There are a great many things that we left behind in the Victorian era, but unfortunately forced marriage continues to exist. There are brides (and grooms) with the same quietly desperate stare as The Reluctant Bride, horrified by their future, possibly surrounded by family members who are comforting/cajoling/coercing them into a marriage they do not want. And without consent, it is a forced marriage. Without consent, that marriage is a crime. It’s amusing to smile at the quaint beliefs of the past, but it’s vital that we continue to resist their legacies in the present.

Written by Alex Carabine

Leave a comment