How do I review something so raw and biographical as the multimedia comic, Cash Cow? As a scholar of the arts and humanities, I’m used to assessing fictional gambits like symbol, metaphor and narrative. But this is real. This happened to a living girl – a child – and it’s happening to other children even as I write this blog. And yet, if Grace had the courage to tell her story, then I should have the strength and the sensitivity to witness it and share it with you. Because we can’t heal what we can’t see, and hopefully, together, we can find ways to be part of the solution for forced marriage.

[Trigger warnings: rape, violence, threat. The images in the comic aren’t gratuitous, but the content is disturbing and may upset some readers. There is an excerpt from the comic that depicts assault, and I discuss rape in this blog post, but not in detail.]

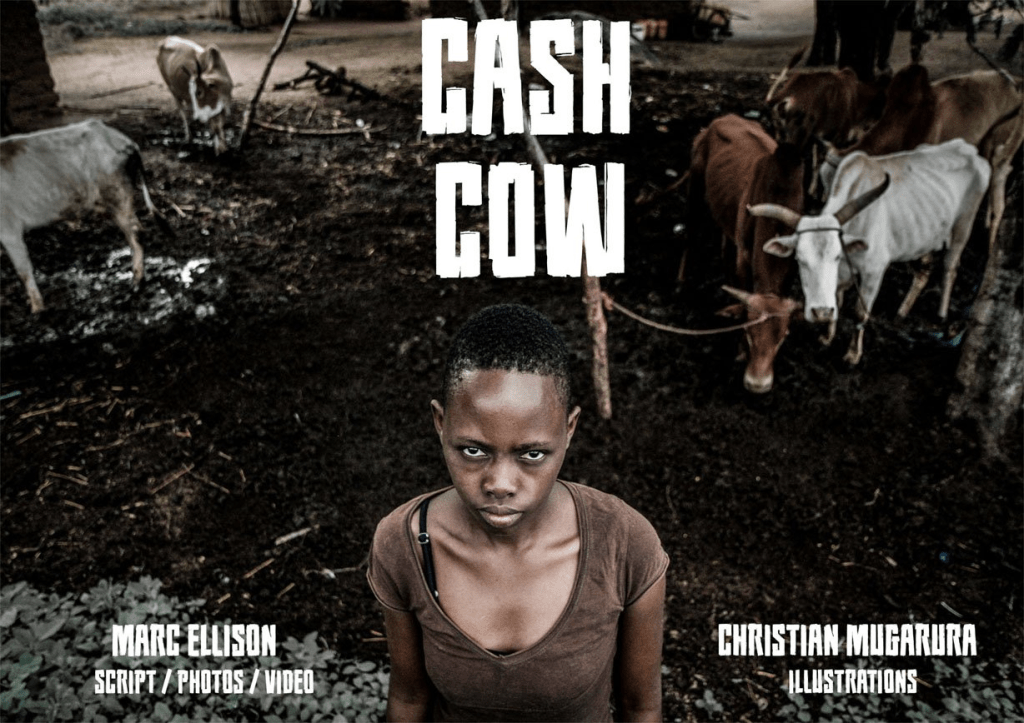

Cash Cow (by Marc Ellison and Christian Mugarura) tells the story of Grace, who was forced by her family to leave school and marry a stranger. The cover is particularly powerful. Grace is photographed from an elevated perspective so that she looks up at the viewer. Her gaze is austere and unflinching. The height of the camera gives the impression that the viewer is taller than Grace, that we’re looking down on her. My interpretation of this choice is that it is to position us as an adult in relation to her, perhaps so that we are aligned with one of the many adults who hurt Grace, or failed her. We, the readers, are witnesses. We may even be culpable. There is a vulnerability in the girl’s pose, and yet Grace’s stare is a challenge. Personally, I don’t believe in the universalising concept that trials and trauma ‘make you stronger’. Perhaps this is true for some individuals, but not for all. I think the sentiment is a balm to soothe those who don’t know what else to say in the face of such tremendous suffering. So, I won’t presume to know Grace’s strength, though she has survived so much. But I will admire the force of her gaze, and the power in the composition of the cover.

Because it isn’t just Grace in the photo. She stands in the churned dirt of an animal enclosure, with a small herd of tethered cattle visible behind her. Directly above her head and no wider than her narrow shoulders is the title: CASH COW. What a pertinent and brutal phrase. Most English-speaking readers will recognise the significance of the saying, even as they might not understand its full implications in this context. Now, I warn my undergraduate students against using dictionary definitions in their essays constantly, but today I’m going to break my own rule and offer the Merriam-Webster definition of ‘cash cow’ here:

Cash Cow (noun):

- a consistently profitable business, property, or product whose profits are used to finance a company’s investments in other areas

- one regarded or exploited as a reliable source of money; a singer deemed a cash cow for the record label.

There is a deliberate ambiguity in the title and the cover because of the presence of the animals behind the girl. Yet, once you understand the context of the title in relation to Grace’s story, how awful it becomes. Grace is the exploitable resource, as are all the girls like her. Not only will her marriage bring wealth to the family, but the wealth is manifested as cattle. Her dowry is a herd. Before you even begin to click through the digital comic, the cover brings home how harrowing and dehumanising a crime forced marriage is. How horrifying that a daughter can reach puberty and cease to be a beloved child and become a thing to be bartered.

“We are the cash cows that can alleviate the poverty of our families.”

– Grace, Cash Cow, p.4

The multimedia nature of the comic is fascinating and impactful. One of the things we wish to challenge with the Drawing on Forced Marriage comic project is the idea that comics are in some way frivolous, that they are neither as serious as literature nor film. This is not the case. Images and narrative together can be influential – consider how we first learn to read, with picture books. We are primed to understand the world through the union of word and image. Because of this, comics are uniquely positioned to tell powerful stories like Grace’s. However, there is one stubborn aspect of comics that is hard to shift: the assumption of fiction. And, full confession, even as I began to read this comic online, I had the unvoiced and therefore unchallenged subconscious opinion that what I was reading was a piece of fiction. It might be inspired by true events, but I thought it was nevertheless a work of imagination. The photographs were my first clue that this might not be the case, though I’ve come across photo-comics in the past that used models to tell their stories.

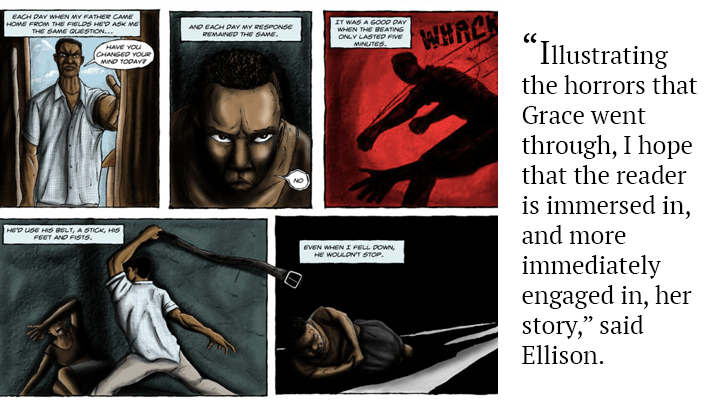

Then, I saw the embedded video links (keep your eyes open for these, they’re subtle if you’re not expecting them). When clicked, these link to real interviews with the subjects and experts of the comic. Artwork, photography and documentary are layered over each other in the text, telling a complex and compelling narrative. Where readers may need distance to process what is happening, the creators utilise artistic representations to move the story forward (Grace’s rape, for example, is drawn, and it is upsetting without being unnecessarily graphic). When the reader might become too complacent, a photo or a video appears to give either visual information, a piece of data, or to recount a memory in the first person. This palimpsestic layering of illustration and experience makes it impossible to forget that the comic might be art, but the situation it depicts is all too real.

I appreciate how closely the creators of the comic kept to Grace’s story. It is, after all, her life. And I don’t want to go into too many narrative details, as I think the comic is best experienced without preconceptions. However, by the end of the story, I was left with a question the text didn’t address. Grace’s father acknowledges that forced marriage is wrong, that he succumbed to the pressure of Sakuma tradition when he made the decision to force his daughter, violently, to marry a stranger. I’m glad he came to this realisation, albeit too late for Grace. Yet I wonder – where are the mothers in the comic? And I ask this not through some subtle misogyny that dictates that mothers are more accountable than fathers for the well-being of their children, but because I can’t help but ask: were they victim-survivors of child marriage, too? After his realisation, did Grace’s father ever look at his wife and see her experience of marriage differently? And how do the mothers feel when they watch their daughters torn from their family homes by traditions that will cause their children such anguish? Anguish they, themselves, have experienced first-hand. My heart goes out to the trafficked girls who grew up with their forced-husbands, and who must watch as the cycle begins again with their daughters.

Grace, at least, was able to break free of the cycle, though she fears for the safety of her little sister. She herself became a mother to a little boy. As I’ve noted, the comic is a depiction of reality, so there is none of the narrative closure we might wish for in such a story. No neat happy ending. No triumph of irrefutable good over indisputable evil. But I hope that Grace is able to make a future for herself and her son, and that the little boy breaks free of the cycles of Sukuma tradition that his grandfather recognised too late. Photo, art and video; this multimedia comic is a powerful and haunting testament to Grace’s resilience, and to the importance of ending forced marriage wherever it occurs.

Written by Alex Carabine

Leave a comment